It’s 1989, and holed up in a grimy tenement building in New York’s Lower East Side is a travelling psychic who claims to be able to tell anyone the date they will die. The four Gold children, too young for what they’re about to hear, sneak out to learn their fortunes.

Over the years that follow, the siblings must choose how to live with the prophecies the fortune-teller gave them that day. Will they accept, ignore, cheat or defy them? Golden-boy Simon escapes to San Francisco, searching for love; dreamy Klara becomes a Las Vegas magician; eldest son Daniel tries to control fate as an army doctor after 9/11; and bookish Varya looks to science for the answers she craves.

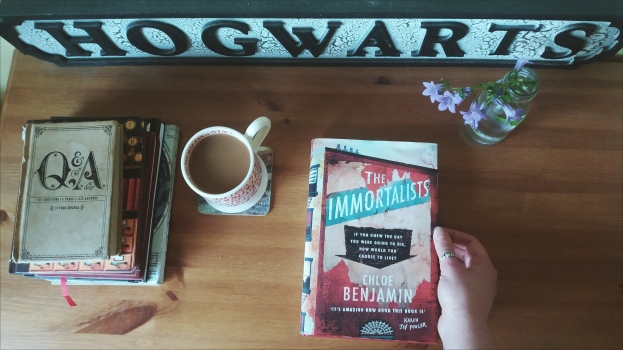

A sweeping novel of remarkable ambition and depth, The Immortalists is a story about how we live, how we die, ad what we do with the time we have.

My god. The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin is not a novel to be entered into lightly. I say this as someone who did – grabbing it because it was a Belletrist book club pick I couldn’t afford at the time they were reading it, without really considering what the summary actually meant. Prepare to come face to face with all your existential anxiety because this is a book about death.

But I still think that you should read it.

To be overly honest and unnecessarily grim, whether we admit it to ourselves or not, life is really defined by its finiteness. That fact, and the crippling panic that comes along with it is something that the majority of us are able to ignore most of the time, but in her clever, tragic, depressing, ironic and at times highly frustrating novel, Benjamin tackles a version of life with that deliberate ignorance removed. Bored one day during the summer, the Gold siblings make a decision that will define the rest of their lives: they find out (or think they find out) exactly when they will die, and in doing so, lose the ability to think about almost anything else.

After our introduction to the Gold family, the book is separated into five sections; the beginning, and then four periods of time, each following a Gold sibling through the final years of their lives (or are they?) as predicted by the fortune-teller. How they each respond so differently to the fortune-teller’s prophecy is a credit to Benjamin’s story telling: Simon’s panicked rush to the finish line, determined to get everything he can out of life before his time runs out; Klara’s fatalism, brought about by her undiagnosed mental health problems; Daniel’s aggressive denial; and Varya’s career, built around a desperate search for a way to extend human life – ironic, as she is the only sibling prophesied to grow old.*

*not a spoiler. You find out in the first couple pages.

There are so many interesting things in The Immortalists, but perhaps one of my favourite elements was the way in which Benjamin, no matter how tragic the family become, never once let the Golds off the hook. As they turned inward, able to experience only their own grief and suffering, Benjamin, as if from a great distance, shouts to them about the other pain that exists in the world. I’m not convinced they ever heard her, and the truth and the frustration in this felt very authentic. As Simon navigated the world as a gay man in the seventies he is unable to see – though repeatedly told – that The Castro in San Francisco, the place where he has finally found his home, excludes Robert, his black boyfriend. Klara is unable to look past her own personal tragedies to see those of her partner, Raj. Born in the slums of Bombay, his father gave everything he had to send him to the US and then died before he could follow. Though he tries to make the point to Klara, and to other members of the Gold family, they never quite grasp that there is pain in the world that is structurally built into it, and just as valid as their own.

The Immortalists is a difficult, upsetting, but ultimately beautiful read. Benjamin doesn’t shy away from her subject matter, whether it’s the reality of death and our relationship to it, or the nails-down-a-chalkboard, walking-on-egg-shells, call-screening aspects of being in a difficult family.

It will totally mess you up though, so do read something fun after. I recommend either light fantasy or a YA contemporary romance.