If we want a world that is beautiful, kind and fair, shouldn’t our activism be beautiful, kind and fair?

Award-winning campaigner and founder of the Craftivist Collective Sarah Corbett shows how to respond to injustice not with apathy or aggression, but with gentle, effective protest.

This is a manifesto – for a more respectful and contemplative activism; for conversation and collaboration where too often there is division and conflict; for using craft to engage, empower and encourage us all to be the change we wish to see in the world.

Quiet action can sometimes speak as powerfully as the loudest voice. With thoughtful principles, practical examples and honest stories from her own experience as a once burnt-out activist, Corbett shows how activism through craft can produce long-lasting positive change.

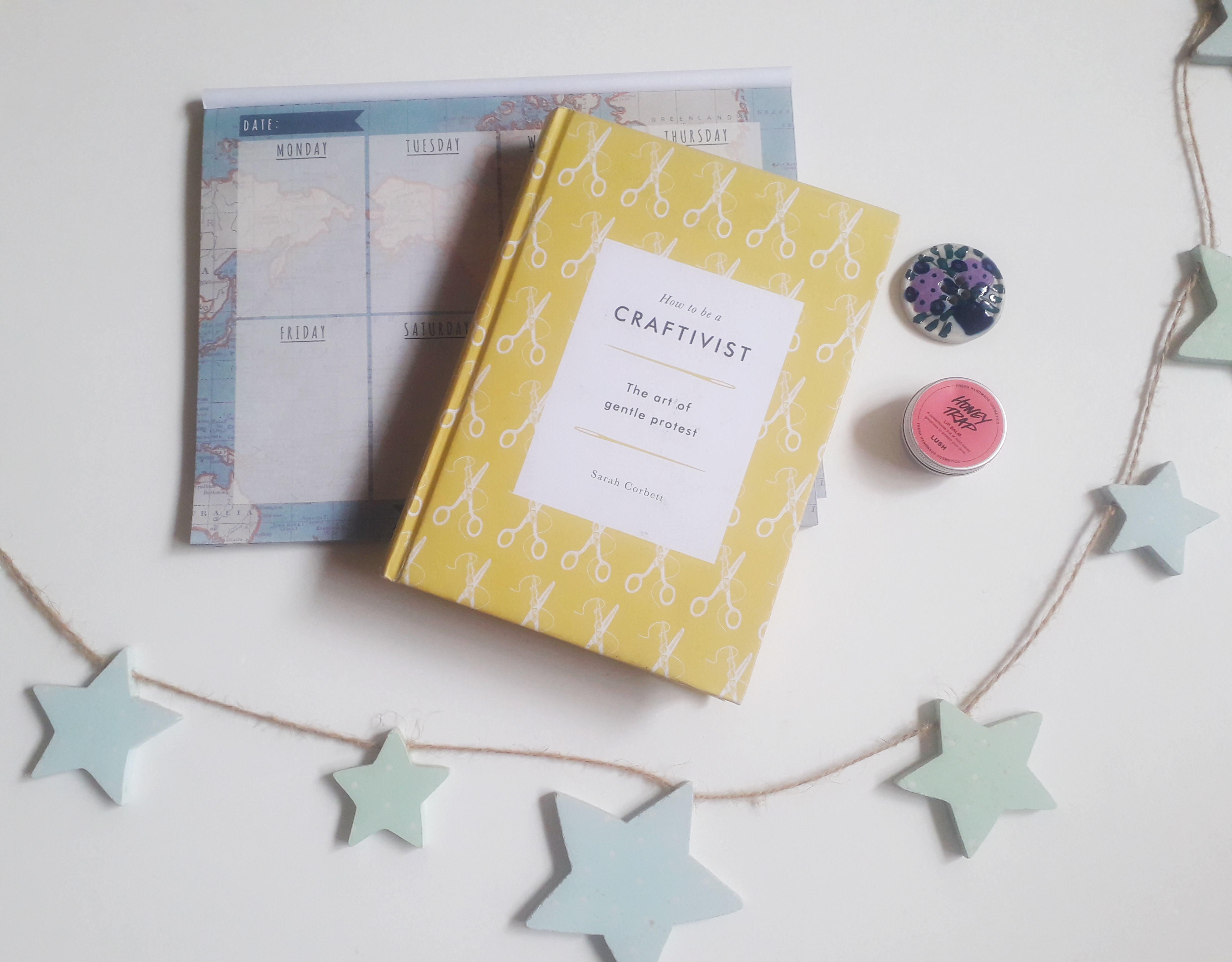

I read How to be a Craftivist by Sarah Corbett for a book club I’m part of, and I have to say my feelings were mixed. Part call to action, part campaign strategy and part activism memoir, the book details how Corbett launched her craftivist movement and the hard won successes of her creative campaigns.

There was a lot about her movement that I liked. For a lot of people, joining a march or – god forbid – canvassing feels difficult if not impossible (I know there can be some privilege wrapped up in this. I’m getting to it). As such, Corbett coming forward with a version of activism that holds out a hand to shy types to whom walking up to a stranger with a petition would feel like actual death felt inviting without being accusatory.

Her campaigns are so creative – with emphasis on using sustainable and ethically sourced materials (rather than, say, feminist slogan tees made by women making less than minimum wage in unsafe factories…). From creating small scrolls to slip in the pockets of garments at fast fashion stores asking #whomademyclothes to messages carefully stitched onto handkerchiefs and sent to local politicians, Corbett breaks down her campaigns stage by stage, inviting the reader to get involved at every turn. She describes how she goes about building relationships with those on the opposing side of the argument, and it is certainly interesting to see how she manages to engage with some powerful people using craftivism, getting them to interact with her work in a way they haven’t with activism before. Through her work she inspires people to communicate with her on an issue rather than go on the defence – something that often feels impossible to achieve.

She also makes a huge point of solidarity over sympathy; so, creating campaigns that centre the people affected by the issue with understanding that they know what the solutions to their problems are. People aren’t waiting for you to walk in and save them, they’re looking for support.

All that said, I have to admit I had a really hard time with her consistent use of the term ‘gentle’ to describe her method of protest. While I know I am coming at this with a certain amount of internalised gender-related garbage, the way her work emphasised being agreeable and non-threatening jarred with me. I wish that Corbett had addressed this, or at least taken an analytical stance on the way that agreeableness has been demanded of women to their massive detriment over time, but she never did.

And then there’s the issue of privilege. Sarah Corbett is a white woman (as am I) so carrying a lot of privilege that I don’t necessarily feel that she addresses particularly well during the book. As it goes on, it starts to feel like she is placing gentle protest in opposition to what she considers aggressive protest, and it was this slowly encroaching binary that I found myself taking issue with more and more. While I think her methods absolutely have value (she has achieved a hell of a lot more than I ever have!), I think that it’s much easier to make a gift for your local politician attached to a very friendly letter, as she recommends, when you’re dealing with a situation you’re not currently affected by. Right? If you’re personally impacted by the ‘hostile environment’ immigration practices or benefits cuts currently screwing over hundreds of thousands of people you’re probably going to feel a lot more like yelling in someone’s face – and I don’t think you would be wrong to do that.

Like I said earlier, craftivism, according to Corbett’s ideals is at least partly about welcoming in people uncomfortable with other forms of activism – I actually fall into this group. I deal with pretty bad social anxiety so the intensity of activism fills me with FEAR. But I also wonder whether we should expect – or even aspire, in this situation – to feel comfortable? Especially if you’re a white woman. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about my own accountability, and in particular all of the various (many) ways in which I don’t live up to my own ideals, and while a lot of actions Corbett presents in the book are great, there was a degree to which I felt she was offering people a way out of getting their hands dirty.

I guess I’m on the fence. There were times while reading that Corbett totally lost me – she tells this weird story about getting dumped by a Tinder date because he ‘didn’t want to date an activist’ until she told him that she was actually an agreeable nice activist, not an ‘angry’ one. I was waiting for her to be like and the moral of the story is fuck that guy, but instead she ended up dating him after she convinced him of her ‘gentle nature’. But at other times her methods really appealed to me, particularly in terms of her tenacity and her approach to a campaign as a long-term commitment.

Have you read How to be a Craftivist? What do you think?